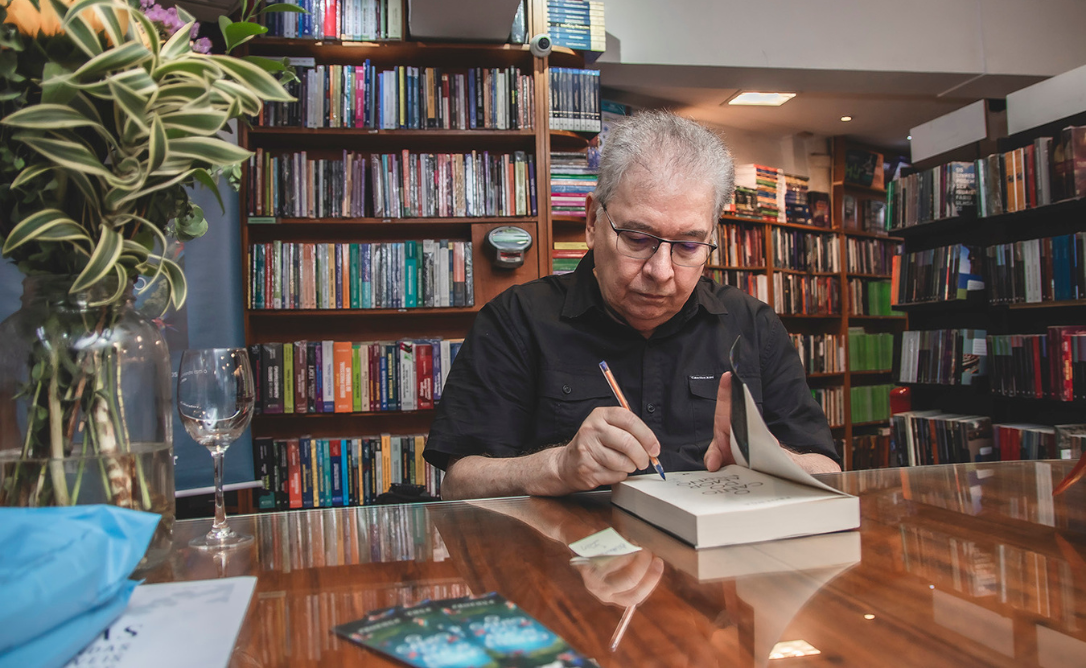

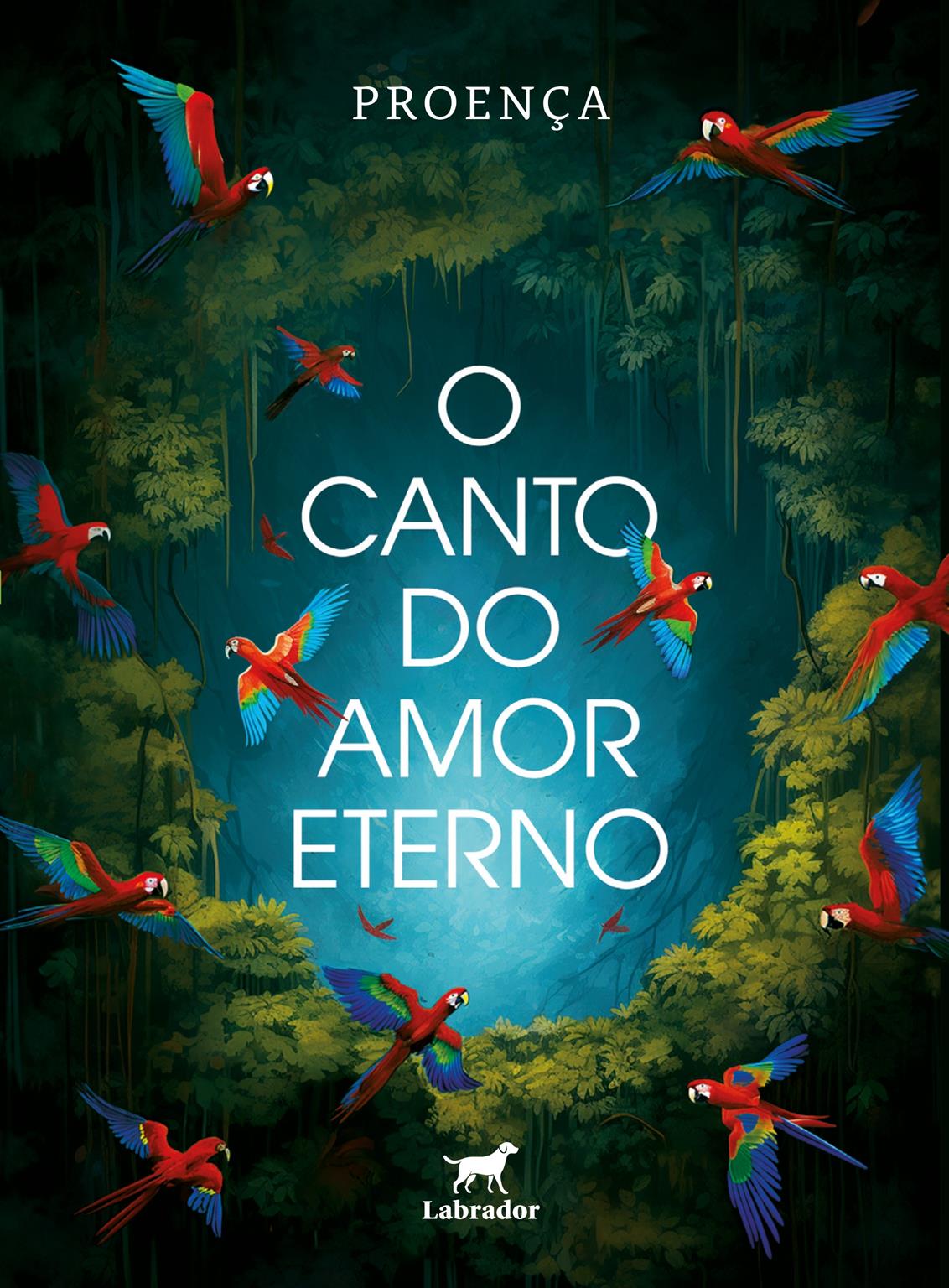

In the novel The Song of Eternal Love, author Proença tells the story of a couple destined to reunite across multiple lifetimes, set against more than a century of social, political, and economic transformations in Brazil and around the world. With passages ranging from the Old Republic to today’s ideological polarization, the book blends history, spirituality, social critique, and lyricism to tell a love story marked by tragedy, reincarnation, and resilience.

Your book weaves together history and spirituality by following Elka and Paulo through different incarnations. How did the idea of using reincarnation as a narrative thread come about in order to explore the impact of historical events on the characters’ inner lives?

The interweaving of real history, fiction, and moral values is the heart of The Song of Eternal Love. Spirituality plays an important role, and perhaps reincarnation is the last hope—for the protagonists and for the country itself—to rediscover the meaning of existence. New lives for Elka and Paulo are new chances to live true love. A new life for Brazil represents hope for a nation free from corruption, poverty, lies, and all forms of tyranny. These goals may seem unattainable to many, but there are still those who believe in the existence of true love and the possibility of a dignified Brazil.

The couple’s journey is marked by pain, revenge, and reconnection. Amid so many social and political changes in Brazil and the world, can love truly be a refuge—or is it also a victim of these contexts?

Emerson said that true love is a prison—and explained: a prison to eternal values. He was surely referring to the kind of love that transcends carnal desire, that requires firm courage, a soul above doubt, and a will that doesn’t bend. True love, when it finds such people, is not a victim of circumstances. But the opposite is true for most of us who inherit from bad husbands and terrible wives degenerate veins, energyless guts, and inconstant passions. We live and want to live only for life’s fleeting pleasures. Walking metamorphoses, as the rocker once said. The one who steers the helm, who shelters himself from utilitarianism and hedonism, walks toward the Emersonian harbor that is worth the journey—and whose waters are enchanted.

The narrative moves between the Old Republic and the current ideological polarization in the country. How do you view the influence of political cycles on people’s emotional and romantic behavior?

I believe part of that question has already been answered, as the book shares the idea that true love is indestructible. But it’s clear that the environment can either provide a supportive space or cause pain and suffering. During the Old Republic, it was easier to identify evil—it was embodied in people and ideologies. Today, it seems the devil is succeeding in his wicked plan against the Brazilian nation (p. 162 of the book).

Elka becomes Isabel and Giulia, while Paulo lives as Jô. What was it like to build these multiple personalities while maintaining the essence of the characters across such different contexts?

It’s been said that writing is a compulsion, not a conscious process. The story is born in the author’s mind and begins to create its own characters, who become independent beings. The real challenge is when those characters assert themselves and take over the narrative. The reincarnations of Elka and Paulo were demands made by the characters themselves.

The book includes references to Manoel de Barros and even a fictional universe within the story, like “The Narrator Caruara.” What role do poetry and symbolism play in the architecture of your work?

Manoel de Barros is one of the finest things ever produced by Jaboticabal. In my humble tribute, I hope to spark the curiosity of spiritually prepared readers to explore his extraordinary work. The book includes stories within the story, offering readers opportunities to reflect on its key allegories. The Legend of the 700 Moons is the seed of true love planted in Elka’s soul. Seu Pedro reveals the dark and dangerous evil that haunted us not long ago. The Bell’s Omen, The Red Dragon, and The Rute Case are fragments of our current reality and glimpses of a terrifying future, depending on the choices we make as individuals and as a nation. It seems we are giving up ethical and moral questions in exchange for emptiness—for nothing. Moral relativism has already led us to the edge of nihilism. Once again, the characters in the story asserted themselves, demanding that these complex yet essential themes be addressed through parables and the genius of Manoel de Barros. I obeyed.

You use different narrative formats, such as diaries and philosophical reflections. What motivated this choice, and how does it enhance the reader’s experience?

It’s a multi-layered book. The details and complex narrative can be appreciated in different ways with each new reading. Books like Crime and Punishment, Ulysses, Stella Maris, and many others would be underappreciated if read only once.

By exploring themes such as trauma, revenge, and empathy, your work points toward healing within a fragmented world. What message do you hope to leave with readers who engage with these intense pages?

The message is in the warning at the beginning of the book, written to Ana but meant for all readers:

“Read slowly, with focus, but with the window of possibilities open. Read as you would read Milton—or better yet, read the way your grandma Joaninha used to read Emerson.” (p. 4 of the book)

If you could sum up The Song of Eternal Love in one sentence that transcends time and reincarnations, what would it be?

A life without love and without meaning is no different than what the Dichotomius schiffleri beetle does while rolling its precious treasure.