In Daughters of Wrath, writer Ronailde Braga Guerra interweaves historical fiction and contemporary reflections to discuss the role of women in the Christian faith. The narrative follows Mary Magdalene, portrayed in first-century Judea as an intense and defiant figure, and Lyana Ahcor, a staunch atheist in the present day who faces family and spiritual dramas. By intersecting the trajectories of these characters, the work explores themes of guilt, religiosity, pride, and reconciliation, revealing feminine strength in the face of pain and the search for redemption.

Mary Magdalene appears in your book in an intense and even defiant way. What motivated you to deconstruct her traditionally passive image and transform her into a woman who confronts even Jesus?

There is much disagreement regarding the identity of Mary Magdalene, who has been described as a prostitute, a noblewoman, and even a suitor of Jesus. Given so much uncertainty, I’ve reached one certainty: she must have been a controversial woman ahead of her time to have her name recorded in the Bible and debated to this day. Add to this what Luke 8:2 reports: seven demons came out of her.

But Luke doesn’t describe when or how she was freed, and in this gap, I began to explore Mary Magdalene in a new light. So, what could we expect from a controversial woman, ahead of her time, and under the influence of seven demons? From this sum, one could only emerge someone intense, defiant, and one who confronts even Jesus, just as other demon-possessed people did.

The work creates a link between a biblical character and a contemporary woman, Lyana. What was the process of bridging these two timelines while still maintaining a common thread of reflection on faith and pain?

The circumstances that create pain don’t change the fact that it’s there, generating its effects. Thus, the process of stitching together two times became simpler than that of constructing them.

This is because, regardless of the time we live in, we are ultimately talking about people, represented by the characters. Both men and women experience their pain and struggle to heal or hide it. Thinking about others, regardless of the time they were in, was what helped me maintain this thread throughout the narrative, sometimes with one foot in the present, sometimes in the past.

Lyana is the president of an atheist organization, but finds herself praying in the depths of despair. Did this scene stem from some personal experience or observation of yours about the paradoxes of faith?

It was born from the combination of two observations: one more profound and the other, not so much… The first refers to the famous Christian proverb that says, “Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old, he will not depart from it” (Proverbs 22:6). Although old, it is relevant and quite accurate. In childhood, our nervous system goes through the most intense phase of myelination, and this defines our personality. In other words, what we experience in childhood is recorded in the nervous system and is reflected in behavior in adulthood.

The second observation comes from the joke “When the going gets tough, even an atheist calls on God.” So, in a pinch, Lyana—a former Christian—retraced that path. And she prayed, like a child.

The title Daughters of Wrath refers to James 1:20. At what point did this verse become the key to your narrative?

It was after the period. I was already in the final chapters, but I still didn’t have a title, and this question began to bother me to the point of hindering my writing. Then, one day, quite irritated, I prayed and told God that He would choose the title. After praying, the question vanished from my mind, freeing me to write. Weeks later, I came across the expression “children of wrath” in a Christian book, and it clicked; it was God’s answer to that question.

Daughters of Wrath was already in review when I came across that expression in Ephesians 2:3. Then, one Sunday, the pastor asked me to open my Bible to a verse. I always skim the previous verses for context, and in doing so, I read James 1:20, which made perfect sense of it all.

The book criticizes distortions of the female role in religious interpretations of the Bible. How do you believe your work can contribute to broadening the discussion about women’s voices and presence in Christian spirituality?

The book follows this line of criticism, but it’s important to emphasize that it comes from the voice of someone resentful of the church and who confuses religiosity with faith. In other words, he sees only what justifies his combative stance, which, throughout the narrative, is challenged.

On the other hand, such a stance “shakes” other characters who feel wronged but remain in this position of victims of the wrath of men (of humanity), and do not resort to God’s justice, like Rahab, Esther, and others. So, if you want to have more presence and voice, first have less so that you have more of God’s presence and voice. If He wants to give you more voice, He will. And He even gives you something to say (or write…), but only to those who have ears to hear.

Your background comes from the health and physical activity field, and you’ve won significant academic awards. How does this scientific background influence your approach to writing Christian fiction?

My scientific and academic training taught me how to research and understand textual structure. This experience was fundamental for my first book, Guardian – Awakening , because without knowing how to write a book, I went into research. But this influence ultimately led to the development of the structure.

When I write Christian fiction, I initially put the scientist aside. It’s not that fiction doesn’t require research; I studied a lot of history and other subjects to write Daughters of Wrath . But when writing the narrative, I need creative freedom, to allow myself to experiment and make mistakes without worrying about proven methodologies, justification of the work, peer review, etc. After the creative side has done its part, the scientist comes back to revise and add to it.

You tackle complex themes like rejection, pride, faith, and redemption, but also a glimpse of hope. What would you like the reader to feel upon closing the last page of the book?

That the power to transform into scars the wounds that the wrath of men leaves us is close, just a prayer away, for that is where God’s justice is found for those who seek Him.

This doesn’t mean that life will be a bed of roses, but having hope that God is there, looking at you and hoping that you ask for help, in a simple prayer, like that of a child, is incredible!

Between Mary Magdalene and Lyana, two women marked by pain and a search for reconciliation, which one challenged you the most as a writer — and why?

Lyana had a harder time, because I was never an atheist. I had my ups and downs with God and the church (especially when I entered university, where science is god and being Christian means being ignorant…), but I never stopped believing in His existence, even in the most difficult times. And precisely because I knew that, despite the difficulties, He was by my side, I overcame many of these challenges.

Writing about non-believers led me to research atheism in depth. I learned a lot and think I understood enough to write Lyana. But in the end, I was grateful to be a believer, because when I read, listened to, and interacted with atheists and former Christians (and former atheists), what characterizes their speech—many extremely intelligent—is a lack of hope. Sad. I prefer to be ignorant .

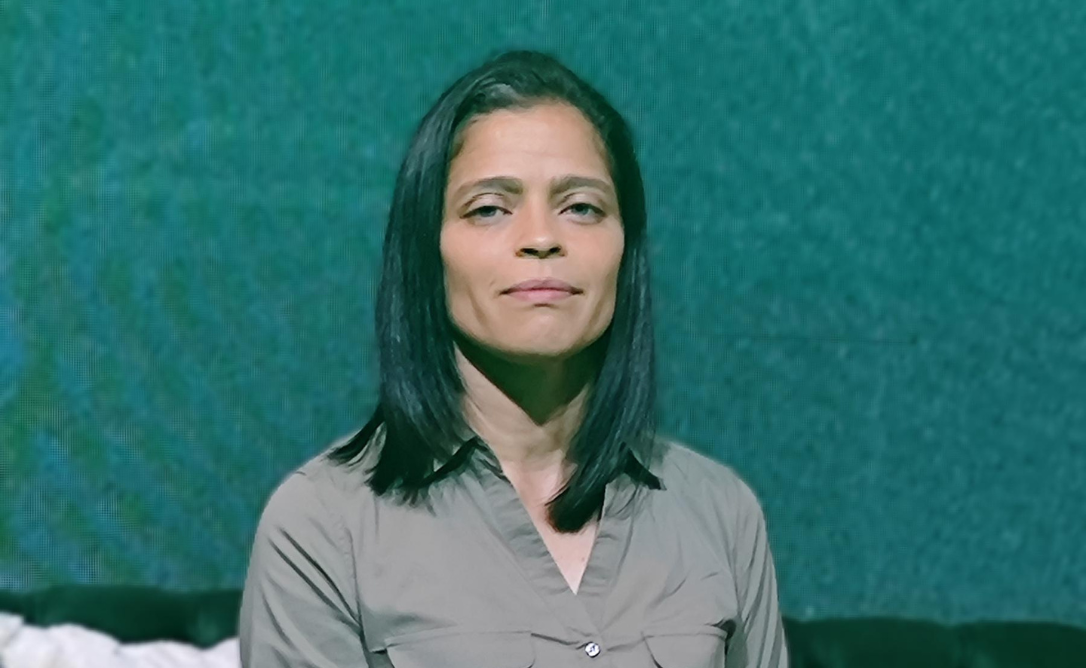

Follow Ronailde Braga Guerra on Instagram