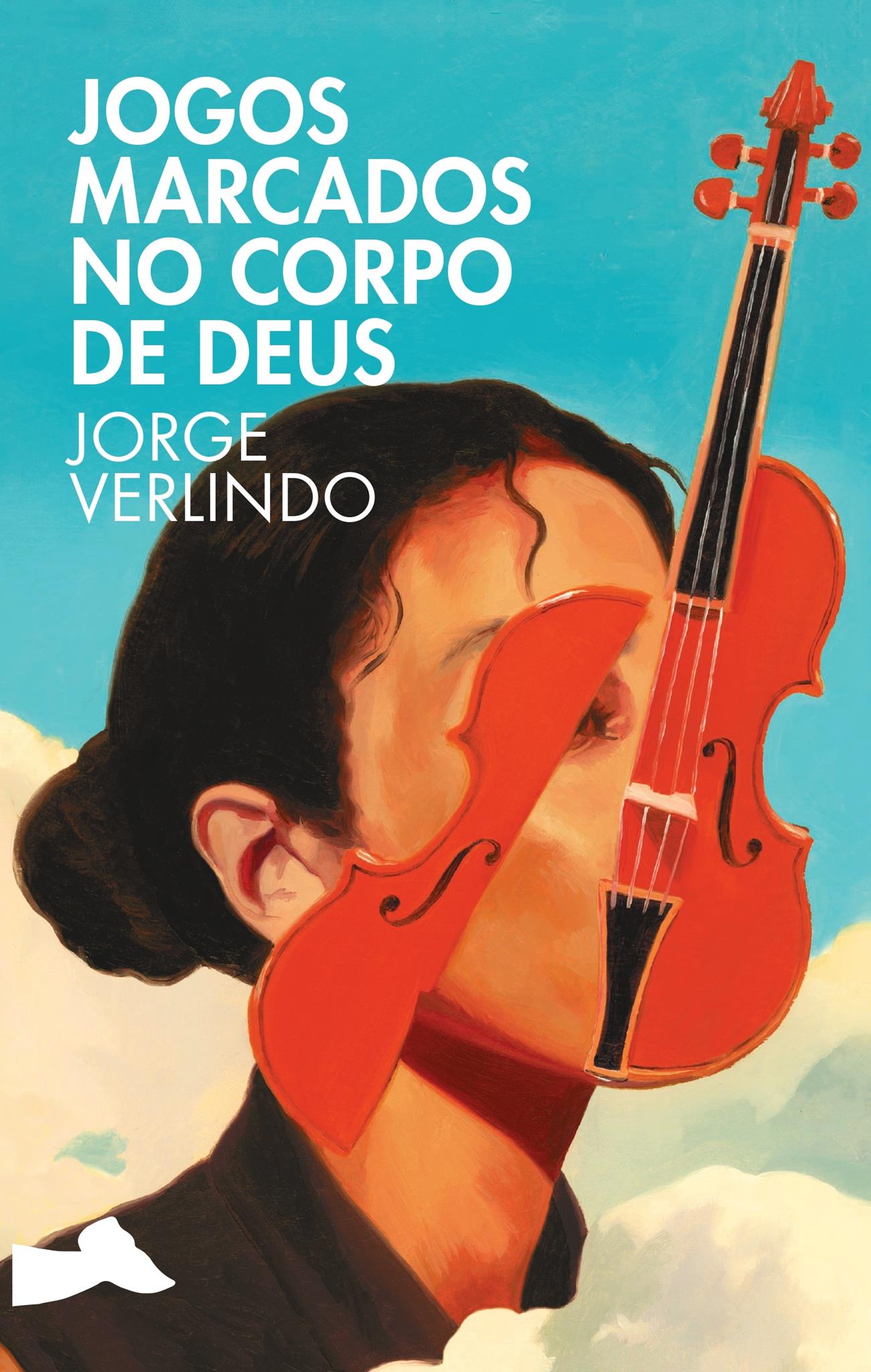

Exploring the invisible layers that shape human existence, writer Jorge Luiz Franco Verlindo debuts in literature with the novel “Games Marked on the Body of God,” a dense and poetic narrative that delves into the emotional gears of everyday life. Set in the middle Tapajós region, the book intertwines the stories of four characters marked by existential crises and intergenerational traumas, leading the reader to reflect on racism, abuse, and the silent mechanisms that sustain human suffering. Combining his background as a musician and his interest in the psychology of trauma, Verlindo constructs a work of innovative structure and almost musical rhythm, where each voice reveals a fragment of the collective soul.

The book’s title is provocative and almost metaphysical — “Games Marked on the Body of God.” What kind of mark did you want to reveal with this metaphor? Is it an indictment, a mirror, or a consolation?

When I started looking for a title, the text was already quite advanced. I was looking for something that would open a window into the work for the reader before they even began. That’s how this title came about, mostly because of Maria’s questions, as she struggles to deal with the contradictions of reality and is subject to senseless suffering. It’s a provocative title, both because it sets up a scene and because it prompts the reader to reflect on it.

Her narrative reveals how small human decisions can be linked to larger forces—social, psychological, or even spiritual. Do you believe we truly have free will, or do we simply learn to play by the rules of the game?

That’s a great question. I believe that free will and subordination are concepts we created long ago, with the mindset of another era, to try to explain our condition. The condition itself is immune to names; it exists, it oscillates, sometimes it gives us freedom, sometimes it overwhelms us. And, because we have this atavistic difficulty of not having control over what happens, even if we put names to it, we are left in agony. And this is where this narrative comes in: it doesn’t have the obligation to give an answer, but to investigate, to open space for the reader to experience, to witness. Meaning has this thing about being much more something attributed than something found. It seems to me that this game of discovering one’s own meanings through the forces embedded in the narrative is one of the book’s gateways.

Maria breaks the cycle and reconfigures her role in the “game.” What does this gesture represent for you—as an author and as an observer of the real lives of so many women who face similar stories?

For me, this breaking of cycles is one of the callings of human beings in general, regardless of gender. You see, in psychoanalysis, that the refusal to break a cycle leads to a compulsion to repeat. Or, as Jung said, “what you resist persists.” In my opinion, the act of breaking cycles is a reaffirmation of the individual’s connection to their own life, a further step towards becoming who they are, to use Nietzsche’s words.

The narrator of the novel is not omniscient, but someone who doubts, hesitates, feels. Why was it important for you to give a human face even to the very voice that drives the story?

This is a question that has been on my mind for a while. Although I adore books where the narrator is a “disembodied voice,” I’ve always had the urge to imagine what it would be like to invite the reader to wander through the story, to give the reader the opportunity to see the world as a story and vice versa. And moving the narrator away from the omniscient figure is one way to do this. Alain de Botton reflects on this in an interview, saying that this format of a disembodied narrator is a consolidated resource from the 19th century, but it wasn’t always that way. If you look at Don Quixote, you’ll see that Cervantes uses various resources to subvert it. I feel there’s a richness to it, not a rule.

You also have an artistic background in music, and the press release mentions the musicality of your writing. How do you translate sound into words? Is there an emotional score behind the prose?

Good question. When you start to delve deeper into a discipline, you begin to see similarities with others. For example, public speaking has rhythm, melody, and notes. You can give a lecture in A minor or G major, for example. And this is replicated between disciplines: when they say that a passage of music is more “sunny,” they borrow descriptive elements from the visual world from the music. For me, this started as an experiment, early in the writing of the book, when I was trying to give form to the characters. It seemed possible to think of them as instruments, with timbres, playing melodies in specific rhythms. Since I had already composed some albums up to that point, I did the experiment and it worked.

The book delves into themes such as trauma, abuse, and racism—deeply painful subjects. What was the process like of writing about collective wounds without turning them into something merely tragic?

Here, you’ve touched on a very important point that actually happened. The early stages of writing fell into a catastrophism and drama that would have made the work indigestible or created an agenda for resentment. I had to stop for a while to rethink this, because that wasn’t the intention. One hypothesis is that our system, from the outset, agendas us towards resentment. For what we didn’t have, for what we aren’t. Even more so today, with the media itself giving us news about what we should be, who achieved it, etc. But if you investigate internally, you’ll see that the opposite movement is what reconnects you. The wound doesn’t break you; it gives you the chance to be greater, to know yourself. We have a fantasy of integrity, exploited and which generates prosperity for certain groups. Thinking of scars as marks of damage (and not as proof of overcoming) doesn’t honor the time we spend here. Anyway, that’s where this reshaping of the narrative came from, which seemed natural to me. I don’t think I would have felt at peace if I had followed the other path.

Your work engages extensively with trauma psychology, EMDR, and Internal Family Systems. To what extent is writing, for you, also a form of therapy—both personal and social?

Great question. If I say it’s therapy, I’m reducing literature and therapy to a single sentence. Of course, that’s not what you asked, and your question is essential for reflecting on the work and on art. I sought out readings about trauma because I felt a need for verisimilitude in the work: in the physics of suffering on our hearts and minds. It was an investigation. And I think “investigation” is the word that establishes the bridge between art and the sciences of the mind. One investigates to create a work; one investigates to understand oneself. If we take this starting point, I would say that art and therapy are excellent opportunities for investigation, for opening up space within oneself and for opening up the map of life’s territory.

If “Games Marked on the Body of God” is an invitation to introspection, what would you like the reader to feel upon turning the last page: unease, relief, hope—or simply silence?

When I started writing the book, I admitted I had more questions about it. Then I went through some hiatuses to understand where the work was heading, and to achieve that, I needed to abandon the questions. Notice that I talked about investigating just now, and now I’m talking about abandoning the investigation. That’s right. Both gestures complement each other. What I decided then was to honor the initial investigation, about suffering and meaning, and leave the feedback, the perception of it, to the reader. And we are in that phase. Some of the reactions that reach me are of reconciliation with oneself, of a hopeful emptiness (this exists) in the face of one’s own life, of compassion for others. I didn’t have anything in particular in mind, but it rewards me to have generated a text that opens space for compassion.

Follow Jorge Luiz Franco Verlindo on Instagram