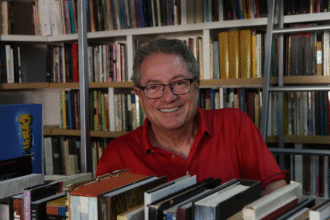

Gustavo Tadeu Alkmim, judge of the Regional Labour Court of the 1st Region in Rio de Janeiro and member of the Association of Judges for Democracy (AJD), presents 23 short stories in “The future awaits you” that explore the intricate complexities of human relationships. With a narrative that transcends everyday life, the author, who holds a PhD in Literature and Cultural Studies, delves into political, social, economic and psychological realities. These stories reveal fears inherent to existence, concerns about death and the emotional challenges faced by contemporary society, using deep and diverse characters. Divided into two parts, the book offers simple, colloquial language, establishing an intimate connection with readers. This work marks the literary debut of Alkmim, who is also a student at the renowned Ivan Proença Literary Workshop.

What are the central themes you address in “The future awaits you” and why are they important to you?

I mainly deal with everyday issues, seemingly banal and ordinary, but which somehow lead the reader to reflect. About life – what surrounds us, what builds us. In short, our perspectives, whether from a social or psychological point of view.

In your book, you explore the complexities of human relationships and the way people exist in today’s world. Can you share more about how the ephemeral society is reflected in your stories?

From the moment we are born, from the first instant, the first cry, we begin to move towards death. This is the real – and inevitable – future that awaits us. We shouldn’t dwell on this inexorability, or else we’ll go mad. Until death arrives, the road may be long. Or not. It may be light; it may be rocky, hard. Whatever the case, on this journey we build and make stories. The collective stories are in the doctrinal manuals. I’m interested in the individual stories within this collective – in our Western case, a consumer, capitalist society which, as such, enshrines individualism. This whole trajectory – from the first breath to death – and our ability to think about it is what makes us human and, therefore, complex and contradictory. Telling about it is what really mobilises me.

How did your background in Literature and Cultural Studies influence the approach and writing of the short stories in “The future awaits you”?

My dissertation and thesis, during my master’s and doctorate, dealt a lot with cultural and social aspects, with an emphasis on literary texts. In other words, there I was able to delve deeper into our contemporary society, particularly Western society, interested in the dialectic that makes the individual the fruit of the system, at the same time as that same individual constructs that same system. So, directly or indirectly, these reflections led me to develop fictional characters who are inevitably inserted in this context – and this, in some way, has some relevance to the story I’m telling, although it’s not necessarily its centrepiece.

One of the stories portrays a man reflecting on his life while looking at his own body in the coffin. What message do you want to convey through this story?

The subject is obviously far from new. Literature deals with it frequently. Perhaps the most emblematic example is Machado de Assis and his Brás Cubas. The attraction of the theme lies precisely in the possible reflection on life and death. Like “who are we? Or “what I did with my life”. The prospect of looking at ourselves in the afterlife is something we have in mind, albeit momentarily, even if we don’t think about it all the time. Hence the invariable questions: “Was it worth it?”; “Would I do it all again?”; “What if I had gone that way instead of here?”. These are questions that I somehow try to leave hanging in the air, at the sole discretion of the reader.

“The future awaits you” presents a variety of characters and situations that reflect human concerns about death and existence. Can you talk more about the inspiration behind these characters and how they relate to these themes?

I tried to depict characters who contain a certain complexity around the life-death binomial, even though they have an apparent simplicity around everyday situations. The housemaid who begins to learn to read, the Portuguese man in the bakery with noble feelings that end up being hampered by an imperative reality, the couple who have to part with their books, the guy trapped in his flat because of the pandemic, the nonconformist communist, the invisible street cleaner, the loneliness of the home- office worker. They all have paradoxes and contradictions that, in the end, portray a human reality – essentially, human.

The division of the book into two parts, “The Tragic Sense of Existence” and “E La Nave Va”, is significant. How does this structure reflect the message you want to convey with your work?

The proposal actually contains an irony. On the one hand, existence and its possible tragedies (the living dead, the lonely bureaucrat, the homeless woman who loses her son, the devil’s church, the family that never shed a tear); on the other hand, “life goes on” (the black lawyer, the couple of uncontrollable lovers, the legend of the woman in white, the need for change). The two parts represent the paradoxes of life – so present in practically all the stories.

You’ve mentioned the importance of keeping the language simple and colloquial in your book. How does this make it easier for readers to connect with the messages you want to convey?

We currently live in a world dominated by the internet and social networks, where abbreviated language reigns supreme, filled with emojis, symbols and acronyms. These are short, fragmented messages, compatible with the times of fast, superficial language and information. The book enters the scene to compete for space with this telematics or to find its own favourable place. I understand that the “dispute” in this case is ungrateful for the book, which demands a specific and particular place. To this end, contemporary readers demand direct and informal texts, without unnecessary and tedious blurbs, and without losing quality. You can’t give up on careful, well-constructed, grammatically correct language, but it should be able to seduce the young reader, allowing the writer to fulfil their ideal: to tell their stories well through short stories or novels.

Is there a particular story or character in “The Future Awaits You” that is especially meaningful to you? If so, why?

I’m going to use an old cliché: a writer’s works are like his children, you can’t favour just one. If I had to choose a special one, it would be the short story “The Ballad of Photography”. Firstly, because it has a “ballad” rhythm, which doesn’t prevail in the other texts. Secondly, I somehow identify with the shy character, a mixture of a 6-year-old boy and a 61-year-old man. It was a story I really enjoyed writing. Of course, I’m present in all my texts and characters, but at the same time I’m not any of them, I didn’t live those stories, and the short stories are definitely not autobiographical or “self-written”. They are pure fiction. Which doesn’t mean that traits, mannerisms, contexts or way of being in any way directly or indirectly portray the writer.

How do you think literature can influence the way people perceive and deal with the uncertainties of life and the future?

Literature is life. Through literature, the reader travels, experiences, gets emotional, experiences anger, strangeness, laughs, cries. Good literature is that which disturbs, causes discomfort, leads to reflection. And induces the reader’s imagination. I’m not so keen on ready-made texts with a closed, moralistic ending. I like literature that leaves everything open to the reader’s judgement and conclusion. The reader becomes the “owner” of the work. Never the passive subject of the relationship. This allows them to think about and mature the text – and to deal with the uncertainties and tensions of life. I see contemporary literature as a place of tension and social non-conformity. A place of doubt, perplexity and enchantment. Francisco Bosco says that the writer writes about nobody. He says, “‘Nobody’ is the impersonality that is achieved when the meaning of reality is illuminated. You write for everyone and for

no-one: when you’ve captured the impersonality of life, anyone can read it, because it concerns everyone’s life; everyone is the same as no-one in particular.” That’s literature.

The title “The future awaits you” has an intriguing connotation. What do you hope readers will take away with them after reading your book and reflecting on the future?

The title is also an irony. What future, right? It’s the unanswered question. Tomorrow, plans and expectations, death? I hope the reader has initially enjoyed reading it. I hope it gives you good moments of relaxation and that you enjoy reading. Writers like to be read, and they want their stories to reach a point of no certainty or conviction. At this point, my “intention” with my stories and characters takes a back seat. What’s important now is the reader’s reception. I can only hope that my writing provokes perplexity, enchantment or doubt in them. Or uncertainty about the future and the present, and sometimes even the past. If I manage to provoke these or some of these sensations in just one reader, or in a few readers, my goal will have been achieved.

Follow Gustavo Tadeu Alkmim on Instagram