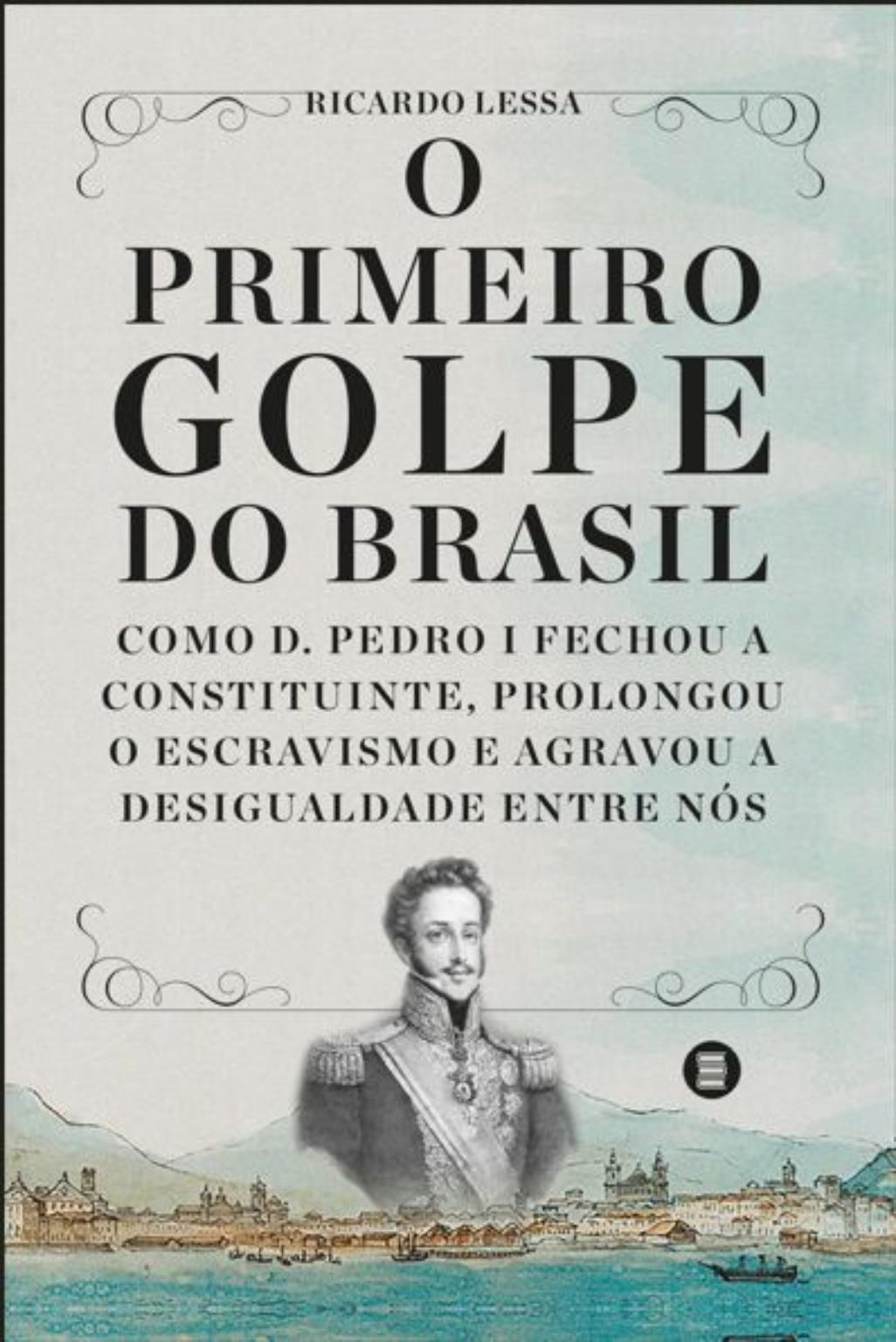

In his most recent book, “O Primeiro Golpe do Brasil”, award-winning journalist Ricardo Lessa explores the 1823 coup led by D. Pedro I, revealing the lasting impacts of this action on the country’s historical trajectory. With a detailed narrative based on extensive research in 19th century archives, Lessa demystifies the heroic image of D. Pedro I, often presented in school books. The book narrates how the young emperor, upon closing Brazil’s first Constituent Assembly on November 12, 1823, persecuted allies, arrested and banished opponents, censored the press, and consolidated his power by surrounding himself with unprepared countrymen and promoting slavery.

Lessa brings to light the behind-the-scenes of a critical period in Brazil, between Independence, in 1822, and Abdication, in 1831. He exposes the dispute between the defenders of aristocratic privileges and constitutionalist republicans, revealing how the victory of delay in this Conflict shaped the last 200 years of Brazilian history. The author, with extensive experience in press vehicles such as Jornal do Brasil, Correio Braziliense, Valor Econômico and on TVs Globo, Manchete and GloboNews, in addition to being an anchor on TV Cultura’s Roda Viva between 2018 and 2019, uses his journalistic background to offer a critical and well-founded view of this chapter in history.

“O Primeiro Golpe do Brasil” presents itself as essential reading to understand the roots of the political and social issues that still permeate contemporary Brazil. With engaging writing, Ricardo Lessa invites readers to rethink the concepts of heroism and leadership, offering a new perspective on the figure of D. Pedro I and the events that marked the beginning of the country’s republican history.

What motivated you to investigate and write about the 1823 coup?

I was born in Rio, I grew up in Rio, the first articles I wrote in Jornal do Brasil in the 70s were still about the history of Rio, where the history of Brazil has passed since 1808. It has always been my interest.

During your research, was there any fact or document that particularly surprised you?

The biggest surprise was that the number of African landings in Rio de Janeiro occurred precisely during the period governed by Pedro I.

You mention that D. Pedro I persecuted allies and banished opponents. Can you give us specific examples of these actions?

The most famous person persecuted was José Bonifácio de Andrada, who went down in history as the “Patriarch of Independence”. After Pedro closed the Constituent Assembly on November 12, 1823, he banished José Bonifácio from Brazil. He spent six years in exile in France. Another highlight is the first lawsuit filed against a journalist in Brazil, João Soares Lisboa, editor of Correio do Rio de Janeiro.

What was the process of accessing and analyzing 19th century archives like to write this book?

This book was long in the making. I was at the National Archives and the National Library. For more than 10 years, as I live in São Paulo, I counted on the collaboration of journalist Ruth Joffily to search other archives in Rio de Janeiro.

To what extent did the 1823 coup shape the political and social structure of contemporary Brazil?

The 1823 coup was the victory of authoritarianism against the first attempt to organize the country constitutionally. Instead of the Constitution being discussed, Pedro and his Portuguese and Brazilian allies, presented with titles of nobility, trimmed the Constitution that was being discussed, created the Moderating Power, an instance above the Legislative and Judiciary, and left the king beyond the reach of laws, which is absolutely beyond the scope of all the constitutions in the world up to that date. Constitutionalism means limiting the powers of monarchs, the king reigns and does not govern.

Here the monarchy managed to get rid of the laws and created this historical premise in the country. Furthermore, the monarchy only sustained itself because slavery was in force. When one ended, the other ended together. Leaving even deeper marks than what is seen in other countries.

In your opinion, why was the figure of D. Pedro I so idealized in school books?

Any power has always wanted to present itself as kind and popular. Despots do not present themselves as cruel. Memory is a powerful area and all those in power want to gain space for their versions of history. First they dominate memory and then dictate society’s behavior, as Susan Sontag, the American thinker, says.

What were the main consequences of the 1823 coup for the press and freedom of expression at the time?

After the closure of the Constituent Assembly, the General Assembly only met in 1826. It was a long night of discretion in which only the monarch, (the word already says, mono, government of one) commanded. With the Moderating Power and the distribution of titles and positions by the monarchy, this promiscuous practice of economic power and political bodies was inaugurated.

How do you see the comparison between the monarchy of D. Pedro I and a modern dictatorship?

Pedro followed the model of Napoleon, who celebrated the Coup d’état of 1788, when he closed the Directory and inaugurated his own dictatorship. From there came the word Bonapartism, which was used about the various coups and attempted military coups that followed in history.

Do you believe that Brazil would have been significantly different if the Constituent Assembly of 1823 had managed to implement its liberal proposals?

Brazil would be different if it had had enough strength to be a republican country, like all its neighbors and the United States. But the social formation that existed at the time, with more than half of the population enslaved and another large part dependent on slavery, did not leave much room for republican ideas. Our republican leaders were savagely repressed, starting with Tiradentes, then Frei Caneca and João Soares Lisboa, the journalist who died with weapons in hand defending republican ideas in 1824 in Pernambuco.

What message do you hope readers take away from reading “O Primeiro Golpe do Brasil”?

May they stop being deceived by monarchists and their disguised, authoritarian and despotic descendants, who every now and then do not want to give up power. Let them see that monarchy and slavery were flesh and blood. And may they be able to rid themselves more and more of these horrible scars in our history. It is necessary to tear the veil of this make-believe and see what needs to be thrown away.

Follow Ricardo Lessa on X