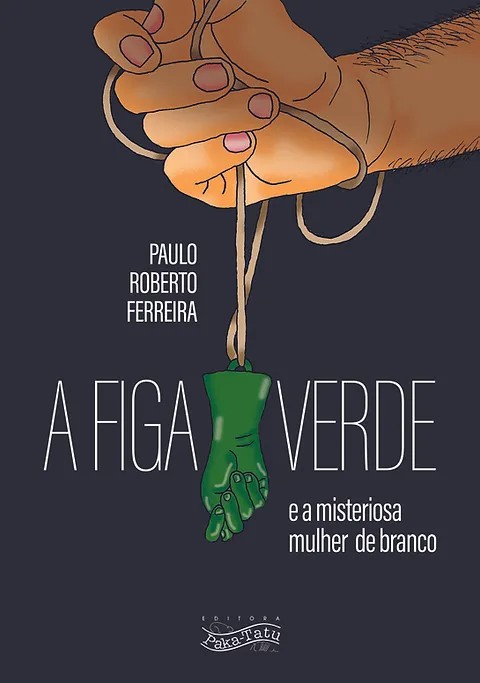

In his sixth book, “A Figa Verde e a Misteriosa Mulher De Branco” (Editora Paka -Tatu), writer and journalist Paulo Roberto Ferreira , born and raised in the Amazon, explores the horrors and cultural resistance during the “years of lead ” of the Military Dictatorship in Brazil. The work, set between 1964 and 1985, reveals the devastating consequences of authoritarianism on the native populations of the Amazon, bringing to light a forgotten chapter in national history.

What the inspired to set your history in a scenario amazon during you years of lead ?

Few people know that the Amazon was the scene of a war in which the Brazilian State and large business groups from the Southeast and abroad invested against the forest, traditional populations and the subsoil of the region. When the military government in 1964 gave the slogan “land without men for landless men”, the start was given to replacing centuries-old trees with grass for cattle, intensive mineral extraction, opening roads and damming rivers for generation of energy. No environmental discussion and no respect for indigenous territories and possessions of traditional populations. The results were impacts of gigantic proportions.

Like you integrated reality history of the Military Dictatorship with fiction in “The fig green and the mysterious Woman in White ” ?

The novel reveals the dramas of ordinary citizens affected during the dictatorial period. A nun punished for working in the workers’ ministry in Contagem (MG) is sent to Conceição do Araguaia; a boy from Maranhão suffers violence in a barracks because he is the son of a sertanista; a young tractor driver participates in the opening of roads (including on indigenous lands). However, there is a figurative element: a mysterious woman, who always wore white clothes. She saves a young guerrilla injured in the confrontation with federal troops and appears – in a real or imaginary way – to several characters in the plot, which included people from the cultural area who gathered near the Theatro da Paz, in Belém.

What was the biggest challenge in creation of the 72 chapters short and in construction of the narrative that addresses the Araguaia Guerrilla and its consequences ?

The concern when writing was to develop a simple story, capable of maintaining the reader’s interest until the end of each character’s plot, hence chapters with a brief narrative sequence. The Araguaia Guerrilla is present because this is a chapter in the history of Brazil that is still little known to the population, especially by new generations. However, the focus of the work is not just guerrilla warfare, but all forms of violence that affected Amazonian populations.

In what way does your search about the period history Did it influence the development of the characters and the plot ?

Of course, the literary production about the Guerrilha do Araguaia helped me in defining the profile of some of the characters, but it also had weight in my own experience as a journalist. I have worked in the Amazon for almost 50 years. I followed the news about the guerrillas from the second half of the 1970s. I met people who survived or lived with the guerrillas. I also had contact with some figures who played a decisive role in the defeat of the armed movement. I followed many struggles between squatters against land grabbers and landowners. I reported lists of people marked for death and covered many wakes of rural leaders and people who supported those who resisted on the ground, such as religious people and lawyers. I saw extensive areas of chestnut trees (Brazil nuts) disappear from the physical landscape in southeastern Pará.

How do you see the relationship between indigenous strategies and resistance against oppression portrayed in the book?

Indigenous populations represent the most fragile part of the forest people. Since the beginning of colonization, they have been affected by white diseases. Violence against their territories and cultural values has been constant in these more than 500 years of contact with the so-called “civilized people”. Because they know the region, indigenous populations are able, in many cases, to camouflage themselves and protect themselves from direct attacks. And the Amazon caboclo assimilated this, which is why he knows, for example, how to avoid a jaguar attack, as stated in the narrative about the character Djanilo .

What role do music, theater, cinema and poetry play in the narrative and resistance described in your work?

Belém’s cultural producers, student leaders and democratic personalities, victims of the military regime, used their spaces and their jobs to subliminally denounce what was happening in the country, mainly in the Amazon. At meeting points, such as Bar do Parque, people talk about their fears and share information that comes from the interior of the region. This raises awareness and motivates the production of musical lyrics, plays, closed-circuit film screenings, the exchange of books that were banned and the organization of entities to support the struggle of peasants, those living on the outskirts and the resumption of student organizations.

Can you talk about the importance of the fig and the woman in white in the story and how these elements symbolize resistance and salvation?

The green fig is an amulet that the father gives to his son when they separate and will be an element of reunion 40 years later. The woman in white is a real and mystical figure in a region marked by legends, myths and enchantments that populate the popular imagination. Both are elements of identity for a people who need to deal with aspects of reality, but they also express their particular way of facing it.

The Amazon is biodiversity and also cultural richness that is configured as a form of popular resistance and this generates a feeling of belonging when sharing experiences. Basically, it’s feeling surprised when considering these elements in the pages of a book.

How did your academic background and experience as a journalist and researcher influence your approach to this book and its topic?

It’s not enough to get to know the Amazon by stepping into its territory. It is necessary to reflect on the entire process of occupation and robbery that the region is experiencing. Universities, research institutes and scholars play a very important role in our education. Figures such as Lúcio Flávio Pinto drew me into alternative journalism in 1975. I was part of the team at “Bandeira 3”, a tabloid that awakened me to the need to know and write about the Amazon. I followed the work of Acre journalist Elson Martins, one of the founders of “Varadouro”, the jungle newspaper. Then I wrote in another publication, “Resistência”, in Belém. I studied at the Núcleo de Altos Estudos Amazônicos/UFPA, and this training has a direct influence on what I write.

Follow Paulo Roberto Ferreira on Instagram