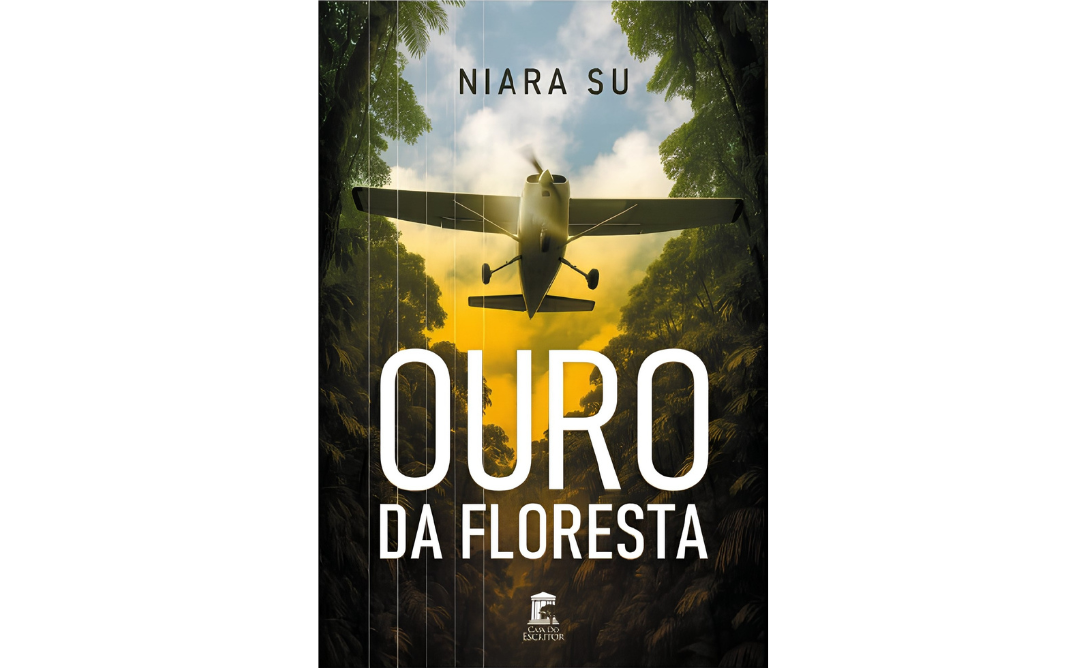

In her debut novel, “Gold of the Forest,” writer Niara Su delves into the depths of the Amazon to reveal the ambiguous brilliance of gold—a symbol of wealth, destruction, and hope. Set in the middle Tapajós region, the work combines suspense, spirituality, and social critique, exposing the human and environmental impact of illegal mining that threatens the forest and its communities.

The narrative follows Jonas, a Rio de Janeiro pilot in crisis who becomes involved with a criminal network and faces a painful confrontation with his own conscience—and with the living forest that observes him. Amidst human dramas, indigenous voices, and ancestral wisdom, the author constructs a story about redemption, faith, and the preservation of life.

Niara Su transforms the original screenplay, which reached the quarterfinals of the 2024 BlueCat Screenplay Competition, into a powerful literary work. “The true gold of the Amazon is the green of its biodiversity—the cure for ills and the guarantee of human existence,” states the author.

“Gold of the Forest” originated as a screenplay and was transformed into a novel. What was the process of translating the story from film to literature like? What did the written word allow that the screen perhaps couldn’t show?

It wasn’t an easy process, as I took the risk of writing without much exposure of the characters’ inner thoughts, something common in many literary works. I chose to keep impactful scenes so that the reader, on their own, could make this confrontation and, perhaps, develop greater empathy for the issues addressed in the book—which are nothing more than an artistic way of denouncing what has been warned about for a long time in newspapers.

The book deals with greed, guilt, and redemption—very human themes. How was it for you emotionally to follow Jonas’s journey, a character so imperfect and yet so real?

It was gratifying to guide Jonas through such themes, as I needed a character who wouldn’t, at first glance, be perceived as evil. Symbolically, Jonas represents all those who, from colonization to the present day, continue to believe that their actions are not a problem, even if guided by other forms of human greed. The fact that there is no blood on his hands does not mean that his actions do not cause destruction to the forest and to the lives of other people.

The forest is almost a living character in the plot. How did you incorporate this symbolic and spiritual presence of the Amazon into the narrative?

The forest, like us, is a living being guided by its survival instinct. When we are in the midst of a struggle and feel an “energy/harmony” from someone in favor of that struggle, we seek out that person. If we feel that the other is working to destroy us, we fight against them, using our weapons. That’s how I worked with the forest, as well as the characters Jonas and Rocha, in the midst of this struggle for survival within the forest, which sometimes rallys one and sometimes attacks the other.

You come from the field of Law. How did this background—with its perspective on laws, justice, and society—influence the writing of the book and the social commentary present in the story?

In law, we need to have an investigative streak, researching as much as possible to properly construct the arguments necessary to claim a right. I used this investigative streak, in addition to my questioning nature, to try to understand this sad reality in our forests and bring this story to life.

The work exposes the open wound of illegal mining and its impacts on the forest peoples. What was the process of researching and listening to these realities like? Was there anything that deeply affected you?

I wanted to impact the reader by properly contextualizing this social denunciation with striking images. Therefore, I researched extensively to bring in real references about illegal mining and the most common forms of violence in this type of environment. What struck me most was an article on an indigenous rights blog about cases of suicide among indigenous women after suffering sexual violence at the hands of gunmen. This reality outraged me, and I decided to portray it in the book with respect and care, without triggers, to raise the reader’s awareness of this serious problem.

The shaman is a character of ancestral wisdom who guides the protagonist towards a spiritual awakening. Where did the inspiration for this figure come from? Is there something personal in this mystical dimension of the story?

The shaman embodies the person with a deeper understanding of the human mind and ends up guiding Jonas, Niara, and their community. I believe that what we call a spiritual gift is nothing more than the gift of dealing with the struggles that our “emotional mind” has with the “rational mind” and vice versa. As a child, I dreamed of being a neuroscientist, and probably the shaman unconsciously represents that desire to be a connoisseur of the human mind.

“The real gold is the green of the forest,” you write. What do you hope the reader will take away upon closing the book—a reflection, a change of perspective, a call to action?

I hope that people will be touched by the book’s final message and see the wise gesture of love from Mother Nature, which I saw years ago when looking at a map of the rainforests around the world, and thus seek to keep this gesture of love alive through their actions.

“Ouro da Floresta” is your literary debut, but it originated from an award-winning screenplay. Looking to the future, do you see yourself continuing in this universe—perhaps adapting the book for film, or exploring new stories with the same sensitive perspective on the Brazilian heartland?

My screenplay didn’t win any awards, but reaching the quarterfinals in a US competition with my very first screenplay showed me I was on the right track. Today I prefer writing books, as they don’t depend on huge budgets to bring a story to life. If my works are adapted for film in the future, I’ll be happy. I don’t see myself writing only about Brazil; in fact, I feel a need to talk about the human mind, about the struggle it wages between its irrational and rational parts. I believe this is the origin of many human problems, including greed.

Follow Niara Su on Instagram