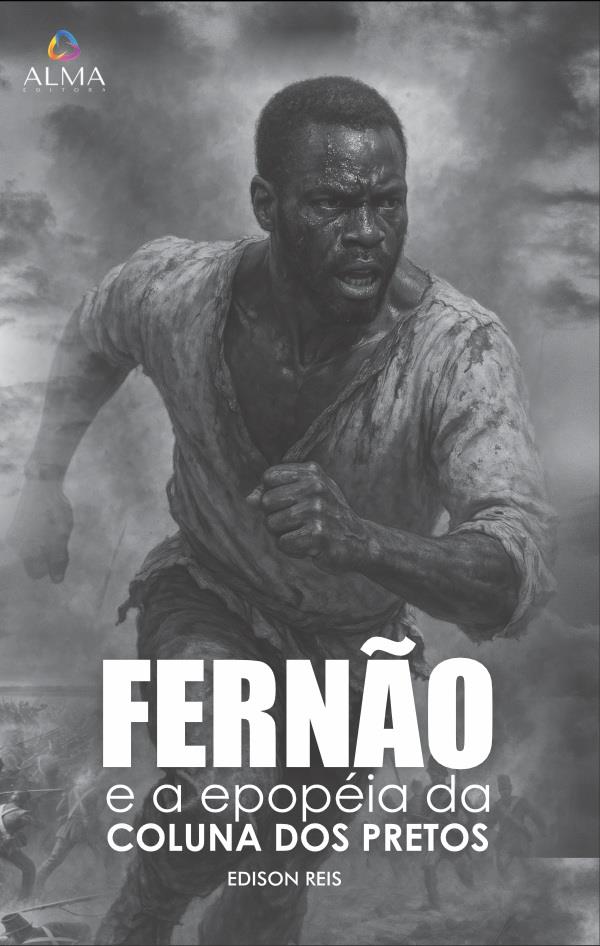

Between earthly battles and ancestral forces, Edison Reis makes his literary debut with “Fernão and the Epic of the Column of Blacks,” a historical fantasy that reclaims the protagonism of Black people in the Paraguayan War and revisits the spirituality of the orishas to retell a story that Brazil has forgotten.

This is a novel that blends spirituality, ancestry, and war. How did the desire to unite the historical epic of the Paraguayan War with the imagery of the orishas and Afro-Brazilian traditions arise in you?

There were several inspirations; it all started with a literature class taught by my professor Geraldo, who brought a newspaper article to class. It was a classified ad from that time. The text described a young slave who could count, was gentle, had all his teeth, was strong, and could work both in the fields and in the big house. This made me imagine an open-air slave auction and what the young enslaved person felt: revolt, pain, nonconformity. I think that was the embryo. Years later, I read a little about what is known about the Zouaves of Bahia; that was the starting point. The incorporation of spirituality came next as a personal need to tell the mythology of the orishas and the religion, the traditions that transcend time, the way spiritual strength sustains the Black people in all struggles, visible or not.

The historical epic and the imagery of the orishas ended up meeting naturally. The war gave me the setting. Ancestry gave me the soul of the story. And spirituality entered naturally.

Fernão is described as a hero forged by pain, but guided by courage. What was the greatest emotional challenge in creating a protagonist who simultaneously carries the trauma of slavery and the destiny of leading a spiritual epic?

Fernão was born from the feelings I had when reading that text in literature class. He didn’t come from dissatisfaction with reality, from the need for a tragic hero model who answers a new call and enters the game of Exu.

The work reclaims the role of Black people—especially the Zouaves of Bahia—in a conflict often erased from the official narrative. What feeling did you have when you realized, during your research, the magnitude of this historical gap?

I felt a mixture of indignation and responsibility. Indignation at realizing how the presence of Black people in the Paraguayan War was pushed to the margins, treated almost as a detail, when in fact they were the decisive force in the conflict. The courage, discipline, and leadership of these men deserved to be at the center of the narrative, not hidden in the footnotes of history.

At the same time, came the responsibility. When you encounter a gap of this magnitude, you understand that you can’t pretend it doesn’t exist. I felt I needed to honor these lives, to give them names, bodies, voices. To bring back a pride that, for a long time, was denied. Writing about them was a gesture of reparation, but also of affirmation: they were there, they fought, they bled, and they died. The history of Brazil is only complete when we give these men back the place that is rightfully theirs.

Exu and Ogum appear as decisive forces in the plot’s development. How did you work to represent these entities with respect, depth, and far from the stereotypes that popular culture still reproduces?

The work was not simple. Before anything else, I needed to learn about them. I studied their histories, their personalities, their principles. My concern was always to treat Exu and Ogum with the utmost respect, far from the distortions that popular culture insists on repeating.

Regarding depth, I saw Exu as a general. In the book, he devises a plan to liberate his people from suffering, which, to me, is a noble action. His other objective was to bring Ogun out of exile, and for that he needed a war. It is this movement that provokes the conflict, brings Ogun back and, years later, paves the way for the abolition of slavery.

My intention was to show these orishas as complex, intelligent, and decisive forces, not as caricatures. They have ethics, they have purpose. Working with this carefully was essential for the book to honor the spirituality and ancestry that inspire it.

Zabelê and Justina represent the strength of Black women during wartime and their absence. Why was it important to you that the feminine had such a strong supporting role in the plot?

It’s important because when the men go off to war, the women stay and life goes on. They supported themselves, the widows of living husbands. It was important because, for me, it’s the history of the war. They were the ones who held up the home, the family, the faith, the memory, and often, the very will to continue living while the men were on the front lines or disappeared into the unknown.

With Zabelê and Justina, I wanted to show this directly. They are women who protect, who heal, who guide, who keep the ground firm when everything around them crumbles.

His book positions Fernão as both narrator and protagonist, not as a figure observed from the outside by official history. What changes—literarily and symbolically—when a Black narrative is told by someone who experiences both the pain and the glory?

The book is narrated in the third person, so Fernão doesn’t tell the story directly. Even so, the choice to follow his journey closely produces a significant effect.

Technically, the third person gives me the freedom to build the world, weave together parallel plots, include historical and mythical elements, and move between different narrative spaces. But at the same time, I opted for a third person who is close to the protagonist, who respects his point of view and follows his inner world without speaking for him. This creates a perspective that, although not narrated by Fernão, maintains the focus on his experience.

Even though he’s not the narrator, Fernão is the central figure. And that changes everything: it removes the focus from the official narrative and places the Black experience as the foundation of the narrative, not as a side note. For me, that’s as important as giving him the first-person perspective. It was also important for me to tell the story from the point of view of a low-ranking Black soldier.

You come from a background in science and innovation in healthcare, very rational and technical fields. To what extent has your training influenced your writing—whether in precision, attention to detail, or the way you perceive the human being?

My experience was of little help in this project, as I work in a highly experimental field. In this project, I was able to bring historical and bibliographical research, the description of scenarios, and work discipline. For many years, I was a nursing professional. This work did give me human elements for the construction of characters and some descriptions of events that are in the book, such as the scene of the first blood transfusion in humans in history.

The book speaks of war, but also of dignity, legacy, and ancestral healing. What feeling do you hope the reader will take away upon closing the book?

That’s a good question. When I started writing, I didn’t think about that; it wasn’t a project designed to send a specific message. This book is my first experience. It was almost a psychographed text, but I hope the reader feels that there were other heroes in the Paraguayan War, that the reader feels a greater respect for ancestry, with a deeper understanding of the strength that brought us here, and with the certainty of dignity and legacy.

Follow Edison Reis on Instagram