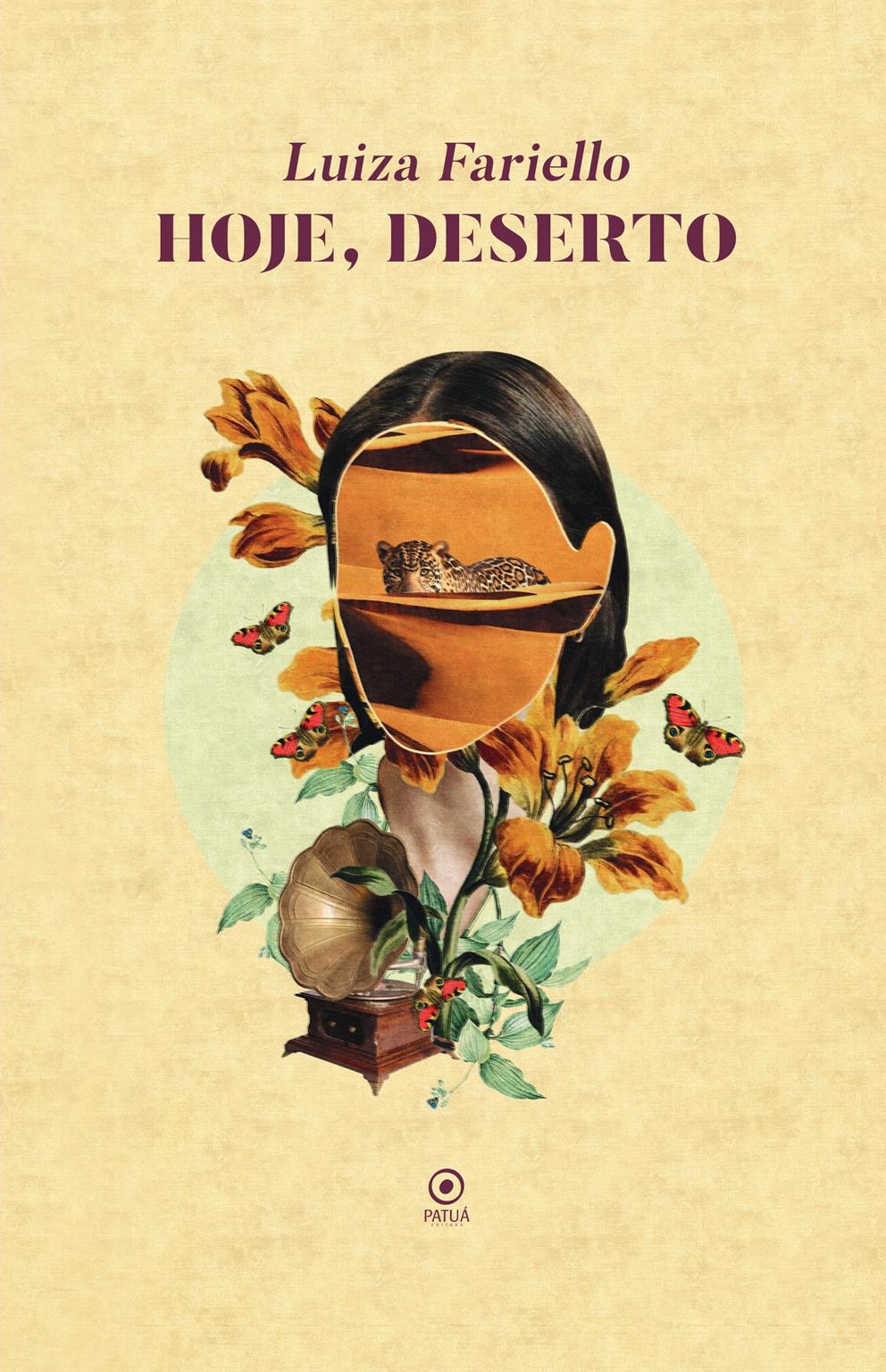

Writer Luiza Fariello , a semifinalist for the Prêmio Oceanos, is launching “Hoje, Deserto” , a collection of 16 short stories that explore the emotional weight of human experiences. Published by Editora Patuá, the work highlights themes such as motherhood, violence and everyday struggle, revealing the complexities of the lives of female characters. Fariello invites readers to explore the silences and internal voids that everyone faces, in a narrative that combines sensitivity and linguistic experiments, set in Brasília and other unnamed cities.

What was the process of creating Hoje, Deserto like? Where did the inspiration come from to explore the “void” and the silences present in the characters’ lives?

I believe that one of the main challenges after writing the stories is the task of bringing them together, since the mere fact that they are together and belong to the same author does not, in my opinion, make a book of short stories. They need to talk to each other, not directly, but in a way that is connected, that they say different things and also the same thing. This theme of emptiness and silence was not planned before writing, but emerged from it. With each new character that I created, I realized that this trait was becoming stronger and stronger and that I had, there, a guiding thread for the stories. I realized that I could explore the silence of the stories and the characters – always leaving room for what is unsaid, for what should be formulated by the reader, based on their life and reading experience – but I could also do this through the choice of language, because that is my main working tool. Thus, I wanted to explore not only the void in existential terms, but also that which arises from the construction of texts , the pauses, interruptions, syntactical inversions, a way of writing that seems natural, but is concerned with leaving space, with creating images that are not completely ready, with suggesting more than judging and presenting a ready verdict; I am a reader of poetry and this helps me a lot in this attempt.

In the stories in the book, you address themes such as violence, motherhood and the pressures of society. How did these themes influence your writing and the construction of the characters?

Since most of the characters are women – and I decided to explore the female universe from the first book onwards –, some themes are almost inherent to them. When you are going to tell the story from the perspective of an ordinary woman living in the present day, it is almost impossible to avoid themes such as social pressure, the unattainable standard of beauty, motherhood and its myriad issues, violence, and sexism. As a woman and a mother, I have also faced and continue to face all of this on a daily basis, so it is ingrained in my daily life and in my writing. I do not believe that literature should be pamphleteering, that is, aiming to raise this or that flag, nor should it aim to spark a certain discussion. However, it is natural for some subjects to arise spontaneously and for discussions to emerge that are quite productive – the struggle that occurs in writing, in fiction, always reflects the struggle of life itself. As the great Brazilian poet Manoel de Barros said, “I invent to know myself”.

You use linguistic experiments in some stories, such as “Inside” and “Outside”. What motivated you to work with different perspectives in the same story?

At the beginning of the year, I took a creative writing workshop with the writer Anitta Deak , which motivated me to do more exercises of telling a story from different perspectives. In the course, the idea is that we do this to then decide which would be the best voice to narrate the story, and then discuss the type of narrator from there. I found it an exercise very interesting and it raised new questions about some of the stories I had already written. However, when I went to write these two short stories that complement each other (Inside & Outside and Near & Longe), I realized that it would be very useful to keep the two voices of the same event there because that could greatly increase the participation of the reader, who in turn would have elements from both sides to choose their version of the facts, to play this game of siding with one or the other, to choose which aspects they find true and coherent in each perspective presented. One of the versions is always that of the child, that is, a childish point of view, more naive and more creative of what is happening. The other would be that of the adult, a more “normal” interpretation of the facts, let’s say. And the surprising thing is that readers, who are adults, tell me that they identify much more with the child’s point of view. Which confirms the idea that we always need to rescue ourselves from somewhere we got lost; our life is more circular than we might imagine.

The concept of “desert” in the book is quite symbolic. How do you see the inner desert as a common and necessary experience for human beings?

The desert, in the book, is more of an internal landscape than an external one – although many stories take place in Brasília, where the drought is severe. The image of the desert was consolidated throughout the stories, an image that I find very beautiful and incredible because it is the beauty that comes from emptiness, from the unsaid, from absence. I believe that we all have deserts inside us, blank spaces that we do not always have the courage to let ourselves inhabit. Loneliness, which is something always seen as something sad and depressing, is different from solitude , which is a beneficial concept of being alone, a state that fosters creativity and spirituality. Buddhism tells us a lot about this, as does yoga, through the exercise of meditation and reflection. The desert should not be avoided, it is a space for self-knowledge; however, the postmodern world takes us further and further away from our essence. Unfortunately, we often end up distancing ourselves from the present and connecting with the superficial, which in addition to being an addiction is also an escape.

One of the stories, for example, “We’re Still Far Away,” tells the story of a turbulent plane trip in which a woman finds herself faced with this emptiness, the inevitable dive into her own memories. So we follow what she does when faced with this despair, this uncomfortable situation, and the idea is for us to put ourselves in her shoes – what do we do with our emptiness?

In your narratives, women are a central figure, with stories of struggle and resilience. How important is it to give voice to these women in your literary works?

As in all areas, many women in literature have been undervalued and silenced. Today, we are witnessing a beautiful process of valuing female writing, of rescuing female writers who were not given the importance they deserved in their time. Female characters are a reflection of what happens in reality, because they always emerge from it, and they return to it as they are read and assimilated by readers. So I believe it is very important to give voice to women in their stories of suffering, prejudice, silencing, and in the many acts of violence they have suffered and have suffered throughout time. At the same time, I try not to judge them for their attitudes or idealize them as heroines – they are who they are, and I want them to have this freedom in the book, so that the reader can feel that. At the same time, I don’t think that this needs to be something fixed in my writing, the female perspective. I’m writing a novel that has a male narrator, an attempt to explore other universes.

As a journalist and Portuguese language teacher, how does your professional experience influence your writing and the choice of topics you cover?

Many stories arise from experiences I have had at work because it is impossible to separate writing from our own story – we are always talking about a place we occupy in the world. As a journalist, I have lived with many incredible people and visited very sad places that have left a deep impression on me, such as prisons. As a public school teacher, I face joy and many difficulties every day. I have many students with severe family breakdowns who have to fight alone to survive at a very young age. I learn a lot from them. The story “Barbie”, for example, was inspired by a comment made by a student during class, when we were talking about self-esteem – she said that when she was younger, her mother would say that if she ate lunch properly, she would have blue eyes like Barbie’s. As a black girl, she would spend a lot of time in front of the mirror waiting for the miracle to happen.

Your first book, Essa palavra eu não falo, was a semi-finalist for the Prêmio Oceanos. How do you see the evolution of your writing from that work to Hoje, Deserto?

The first book of short stories I wrote, which took ten years to complete, was a birth for me as a writer – how difficult it is to have the courage to publish, to believe that something is worth reading! I have been writing since I was little and it has always been an essential activity for me; understanding the world, for me, comes through fiction. I have always felt very uncomfortable at times when, for some reason, I had to distance myself from writing. I wrote whenever I could, even though it was difficult to reconcile with my routine, it was something I had to do. But I kept everything in a drawer and sometimes thought that the time would never come to publish, that perhaps I didn’t deserve it. I was very happy to be in the semifinals of the Prêmio Oceanos and the finals of the Prêmio Candango de Literatura – it was a recognition that encouraged me a lot.

In this new book, “Today, Desert,” I was able to focus on many other factors – I felt more confident about trying different narrative techniques and diving deeper. Now I was able to accept myself as a writer, and that made a difference; it gave me greater responsibility. I wrote with what I had at hand, the everyday stories that wandered through my memory and that I thought should be told. I looked for some poetry lost in the days in the stories, perhaps that is important to say.

What role do you think literature plays in addressing such delicate and complex issues as violence and loneliness? What impact do you hope to have on readers with your work?

I think literature should always provoke us, move us in some way, make us think from other angles, on whatever themes it addresses. I am very grateful when someone tells me that they identified with or were moved by a character, because if the stories are not capable of creating a bridge with the readers’ lives, then they are not worth writing.

The theme of solitude (right from the title, which is ambiguous, the desert as a noun or verb) runs through the stories, the landscapes of the stories. Writing and reading are also solitary activities; I am not afraid to explore the theme of existential emptiness, nor of violence, even though I get hurt by it. Not being afraid is essential to writing, because the process of self-knowledge that comes with writing is enormous, therapeutic. There are themes, for example, that I am afraid to even think about, and I have not ventured to write about them yet.

Follow Luiza Fariello on Instagram