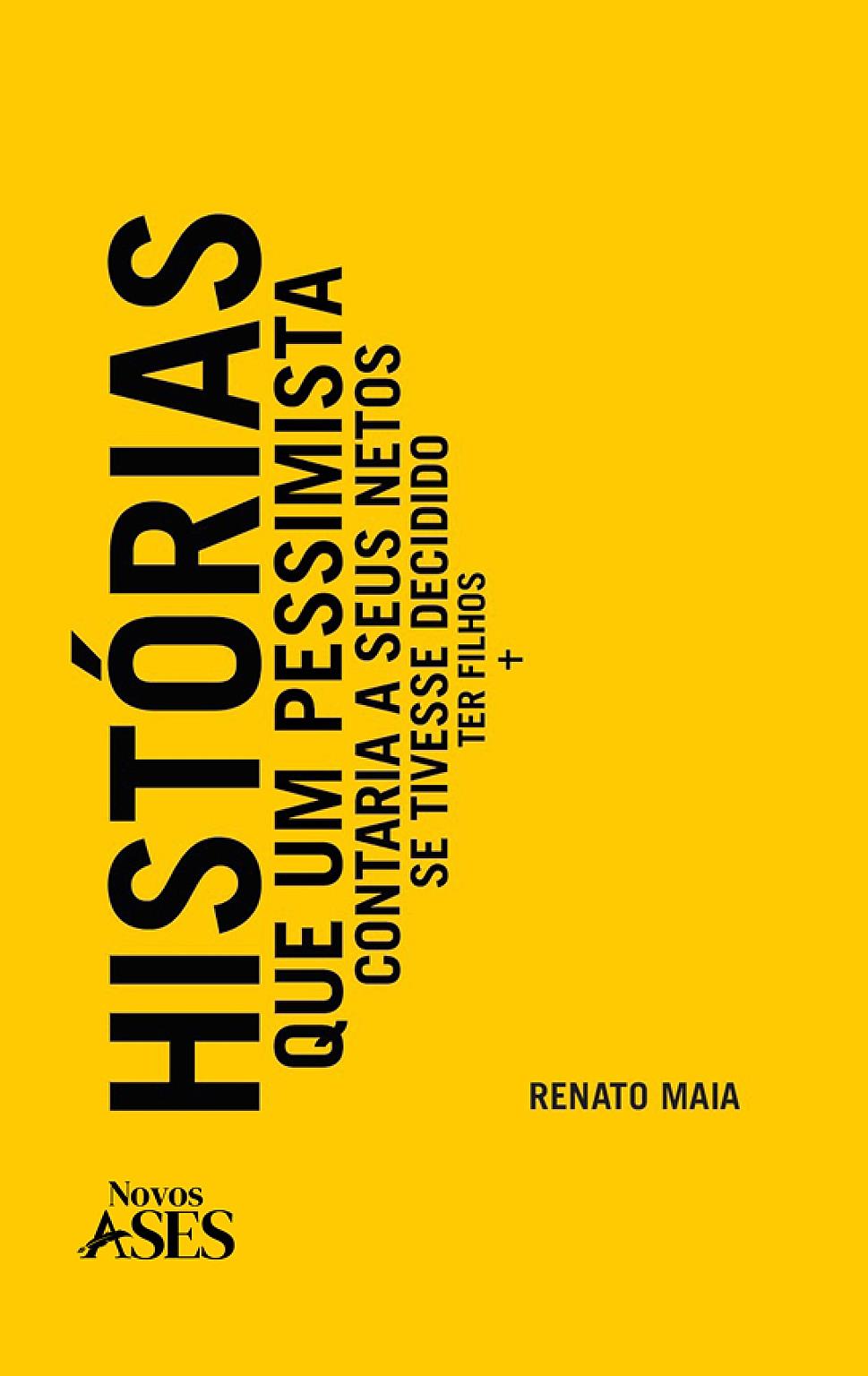

In Stories that a pessimist would tell his grandchildren if he had decided to have children , Renato Maia brings classic tragedy closer to everyday Brazilian life, revealing how drama, often associated with heroes and myths, finds space in ordinary life. With 40 short stories that reflect the challenges of the working class, the author explores themes such as inequality, loneliness and the struggle for survival, mixing melancholy and humor to address the complexities of contemporary existence.

In your book, you discuss how the tragic can also be found in ordinary working-class lives. What led you to write about human suffering from this perspective?

First, I believe it was a question of identification. As much as the themes of classical tragedies are universal, the characters involved are from a very limited and distant sphere from us, ordinary people who are not solvers of mythological beings’ riddles, nor heirs to Scandinavian thrones (to name two of my favorites). Tragedy can also occur in a supermarket queue, for a mother who is beaten by her partner in silence so as not to wake her children who have school the next morning, or while waiting under the scorching sun to visit a father who is in prison. From a practical point of view, I think these things speak more to me than Lady Macbeth’s imaginary bloodstains, although I venerate this image and Shakespeare’s work.

Despite focusing on themes such as poverty and violence, your book finds room for humor. How do you use sadness and humor to create an engaging and thoughtful narrative?

Yes, humor is essential to me. It’s the same thing Guimarães talks about in Grande Sertão: life heats up and cools down, tightens and then loosens, calms down and then becomes restless. What it wants from us is courage. The exercise I try to do in this book and which I invite the reader to join me in is to understand how this courage that makes us go on works and where it comes from. Perhaps one possible answer to this question is humor, which is why in anything that happens , no matter how sad or tragic it may be, in my opinion, there should always be someone pointing out an unusual or satirical aspect of that event, a kind of Titanic musicians offering a playlist for the sinking.

You are inspired by philosophers and writers such as Clarice Lispector and Schopenhauer, who explore the complexity of the human condition. How do your inspirations from these authors come to the fore in the book?

Since these authors are very present in my readings, spaced out throughout my life, I am sure that my imagination is in some way populated by the atmospheres that they created in their works. In this book, there is nothing specifically inspired by any of the philosophers, authors and authors mentioned; what there is is an exercise of imagination and conjecture about how these authors would overcome the narrative impasses and dilemmas that I encountered while writing the book. In short stories in which I narrate in the first person and the protagonist is female, I tried to imagine how the subjectivity present in Clarice’s work would shape the character’s actions.

Many of the stories portray the struggle for survival in the chaos of the metropolis. How do you see the relationship between urban challenges and the feeling of helplessness described in your stories?

I believe that the city and, mainly, the act of wandering around the city is a fundamental part of my creative process. Of course, riding public transportation in São Paulo is not an activity to which we can write odes, but I try to take advantage of the time I am in this environment to listen to and observe those who interest me. To see their impressions and priorities in this insane game of hot and cold that is life. I once observed a couple, and I even based this observation on a chronicle in my previous book “ Allegro”. Ma Non Troppo”, and this couple, apparently just formed, analyzed the calendar for the following year in search of holiday extensions to plan their travels. That surprised me and at the same time I was amazed by this exercise in such marked optimism, in the face of the fragility of life. Every season people come and go, and there are so many stories, disconnected in principle, but that deep down are woven into a common fabric, which perhaps is the hope for some future, even if it is just a long holiday.

You mention that art seeks meaning in the face of despair. For you, is the act of writing an attempt to organize chaos or to find some kind of redemption?

I think it is much more an attempt to organize chaos than to find redemption. I have no hope of redemption. I just want to pay next month’s rent and try to live off the things I love, which are literature, cinema and philosophy. I remember that shortly after the attack on the twin towers on 9/11, I read an article in which the author mentioned that, after that event, the number of gym memberships and the search for healthier foods to eat dropped drastically. That’s it, when we lose sight of the future, everything that keeps us sane loses perspective, despair sets in and the notion of history and process disappears completely. My attempt with this book may be to understand what makes us continue. Does it take an event like 9/11 to completely take away our hope? Or do the small misfortunes and subtle disappointments that we experience day by day, because they are diluted in time, anesthetize us so that we can continue following the rhythm of the waltz? Or are the cathartic elements, like in my case the arts that I mentioned, that prevent us from pressing the red button?

Your stories portray realities that often reflect the lives of those who read them. How do you hope your readers will feel when they see their own experiences in the book?

The impact on others is always a delicate matter. It is difficult to think about the impact I want to create. It seems that I am placing myself above the reader and trying to lead him or her like a puppet. Of course, I am not naive enough to think that the author, when employing a narrative technique, is not, in some way, leading the reader, but given the themes I address in the book, I think that I have less answers with this work than questions. I think that these stories are, above all, an invitation to the reader to try to understand together the reasons that make us go on. If life is, as it so often seems, so full of helplessness, pain, suffering and disillusionment, why do we continue to take our crowded trains and subways every Monday?

The title of the book reflects a pessimistic outlook on life, but it also seems to carry an ironic note. In what way does pessimism serve as a means of revealing universal human truths? And how did the idea for this ironic title come about?

Philosophical pessimism emerged as a response to philosophical optimism (see how Guimarães’s game of warming up/cooling down works for everything), a result of the enlightenment of the 18th century. The figure of the wise Pangloss , satirized by Voltaire in “Candide and Optimism”, is the contemporary #gratilight. An exaggeration on one side of the scale ends up requiring a counterbalance on the other side. So, my exercise in pessimism in this book is perhaps a fight against #gratilight. The irony of the title and the essence behind it is the logical impasse that an exacerbated pessimism can also represent. Just as the reckless optimist is problematic, the radical pessimist also represents a practical dilemma. The consequence of his absolute distaste for life is the extinction of life itself. It is having a work to read to an empty audience .

Many stories are based on small, everyday tragedies. Do you believe that pain has the power to teach or transform, or is it simply part of the inevitable human condition?

Pain does indeed have a pedagogical function. A child who touches fire for the first time does not need a second chance to draw conclusions. But this is not the case of glamorizing pain and suffering as essential and indispensable stages towards successful human development. Not suffering must be much better, but that is where the concreteness of a non-idealized world comes in. In it, what we observe is the inevitability of the experience of human pain and suffering. What life wants from us is courage. Courage can be a variant of the cardinal virtue of Fortitude, which is the ability to demonstrate confidence in difficulties and seek good even in the face of adversity. It is a cliché, but it is nevertheless quite true: you do not make a good sailor in calm seas.

Follow Renato Maia on Instagram